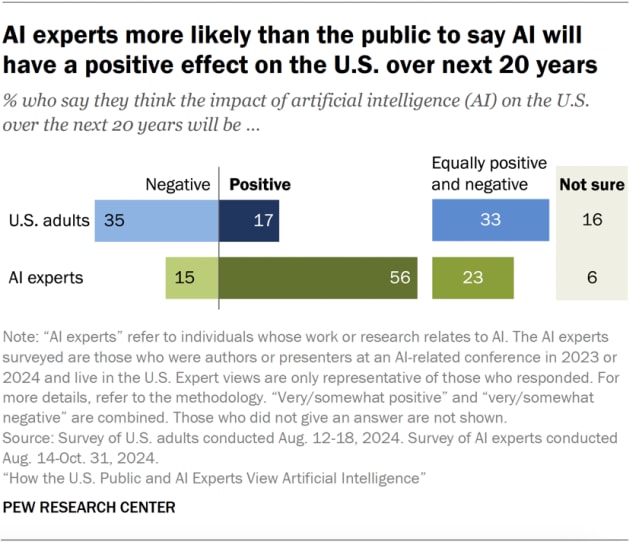

The American public hates AI.

That -18% sentiment puts AI somewhere between fracking (-9%) and race-aware college admissions (-23%).

When asked about AI, Americans worry deeply, especially about specific applications. Self-driving cars polled in 2022 at -18%; AI for tracking worker movements polls at -46%.

But it’s not a salient issue. In Gallup’s “most important problem facing America” timeseries, AI, bucketed into “advancement of computers/technology”, merits less than 0.5%. A quick eyeball shows that AI makes it onto the NYT Opinion page only every couple of weeks. (They seem to publish about ten per day.)

I think that many in the AI safety community dismiss popular opinion as uninformed, reactionary, or misdirected. You might even worry that populist backlash can lead to ineffective regulation that does more harm than good.

But public sentiment could be a force powerful enough to slow unsafe AI development. In this post, I want to outline three mechanisms by which it could.

Public opinion makes it easier for people who have leverage to use it. At the turn of the 20th century, for example, muckraking journalism was a key enabler in Roosevelt’s trust-busting. That reporting directly encouraged policy. But it was a flywheel that both responded to and shaped public opinion.

The journalists, picking up on public resentment towards the trusts, knew that people would buy their papers if they published anti-trust screeds. The journalism fanned further anti-trust sentiment, shifting the Overton window and making more and more stridently anti-trust journalism possible, which, in turn, influenced the public. The same thing can happen with AI.

A culture perceived to be amenable to anti-AI sentiment is also one where people are more inclined to speak up. In AI 2027, for example, the whistleblower leaks the report because they know they’ll be well-received by the population. Later in the scenario, appeasing the public is partly what drives the creation of the Oversight Committee.

Whistleblowers are driven by duty and estimated impact, both of which correlate to negative sentiment. The whistleblowers Daniel Ellsberg (who leaked the Pentagon Papers) and Edward Snowden acted because they believed in their cause, but their belief was surely encouraged by the sentiment in the water, which also evidenced their bet that the message would resonate.

We’ve already seen this in AI. A huge reason why people like Leopold felt empowered to leave OpenAI is because their community (this one) instilled this particular sense of duty and celebrate them for acting on it. It’s much easier to do the right thing if it’s popular. When the right thing is as baseline difficult as whistleblowing, sentiment can make the final difference.

Companies will gladly appease the public. At the height of the corporate activism era, many firms hopped on the LGBT or environmentalist bandwagon once their peers started doing so, because they knew they’d face backlash if they didn’t.

Talk is cheap, but there’s only so much lying you can do. Maybe I’m naive, but I really do think that most people, even at the highest levels, try their best to be coherent. And It’s difficult (though not, alas, impossible) to maintain the self-delusion required to keep consistently saying one thing and doing another.

Oil companies, for example, embarked on ambitious greenwashing during the nineties. They invested millions in rehabilitating their public images. (Did you know that BP stands for “Beyond Petroleum” since 2001?) Later, during the ESG boom of 2015-2020, companies that didn’t at least say they had climate goals suffered in the markets. ExxonMobil, after years of resistance, finally published climate risk reports in 2018 after sustained investor pressure.

You might object that corporate marketing is not the best way to achieve climate goals (or AI ones). That, in fact, greenwashing simply neutralized public sentiment through PR, rather than meaningful change. This is a valid concern. But the alternative to “Beyond Petroleum” was never the shutdown of BP; the alternative was no change at all, not even a superficial one. At least they say they want to be green. Even if these corporations are perfectly capable of maintaining hypocrisy, statements like that are ammunition for activists, investors, and regulators. It’s not the most efficient way to do things, but it’s better than nothing.

Public opinion usually can’t, by itself, create much change. It’s most effective as a braking mechanism on the machinery of politics. Trump tried hard to repeal Obamacare in his first term, and due to public backlash, he’s given up. Sustained and vocal public opposition ultimately scuttled the Keystone XL extension. NIMBYism derives its staunchly persistent power from status quo bias.

This braking force of public sentiment works by applying friction up and down the societal stack. In addition to lip-service from corporations, it forces lip-service from politicians. That can have real effects, particularly in local and state politics.

At the local level, public resentment of AI can cause measures like the facial recognition bans in SF and Boston. It can support ballot initiatives in important cities in California, directly regulating Silicon Valley. It can provide tailwinds for a burgeoning digital NIMBYism in datacenter districts, as we’re currently seeing in Northern Virginia.

At the state level, attorneys general could take advantage of negative public sentiment on AI to launch investigations and file complaints for easy points with the electorate. Negative sentiment could also inspire state-level laws restricting AI training, data collection, or deployment.

The thing about friction is that it’s effective even when any specific measure fails. If companies perceive the public as opposed to AI, they’ll infer that there’s a latent regulatory risk, that some city council member or AG or state senator with a precarious seat might try to position themselves as the “anti-AI candidate”. They will also know that any perceived or actual misstep will make such punishment more likely, and might devote more resources to safety or at least to PR, which, again, is better than nothing.

Unpopularity is an asymmetric advantage. Because public opinion is better at stopping rather than starting, because it’s fundamentally conservative, it can favor safety over acceleration if framed correctly.

(I won’t be attempting to fully prosecute a practical strategy.)

The goal of harnessing already-negative public opinion to increase the friction of unsafe AI practices. The first-order goal is not dramatic Congressional bans or massive protests. While unpopularity might make those things more likely, its primary mechanisms of action are through the thousand cuts of an unfriendly media environment, institutional lip-service, and local regulatory risk.

The general public fears AI (as they should), but it’s not salient. That’s the bottleneck. What those concerned about AI should do, then, is increase the salience of AI, particularly its harms on normal people. This means appropriate messaging: we need people talking about extinction, but for most people, the far more visceral fears are job loss, surveillance, and algorithmic decision-making.

This also means not being too worried about “wrong” concerns about AI, such as the environment, artists’ rights, or (for some) China. I personally dislike the arms race framing that the AI companies are stoking, but they’re making a calculation similar to this one, except optimizing for congressional rather than popular sentiment.

This is one of the key failure modes of stoking anti-AI public sentiment. It can backfire. Arms-race framing and GDPR or EU AI Act-style legislation have already happened off the back of negative sentiment, and it’s possible in the future that it pushes AI companies to safetywash or even pushes them underground.

We shouldn’t uncritically amplify every anti-AI narrative. They can be manipulated by AI companies, as we’re partially seeing with the China framing. And some will definitely do more harm than good. The answer to this counterargument is that I don’t know. I don’t know which specific narratives will resonate, direct attention towards net good interventions, and avoid boy-who-cried-wolf or “sci-fi” dynamics. However, I do expect that negative sentiment directed at the public (job loss) rather than Congress (China loss) is less risky: again, public sentiment is asymmetrically powerful; it’s easier for a mistaken Congress to pass bad legislation than for a mistaken public to force Congress to do so.

So I think it’s appropriate increase the salience of worries like job loss, surveillance, and outsourcing human decision-making. These concerns, sufficiently narrowed or broadened, are realistic, near-term, and directly affect the people, not just Congress. You might worry that these are largely only mundane harms, that they don’t get at the core existential risk that is what makes AI so dangerous.

But I suspect that certain types of mundane concerns lead to friction that is not totally orthogonal to the type that decreases existential risk. Although I can’t argue for it in this post, mundane concerns could lay the groundwork for existential ones, or could provoke responses that reduce existential risk. Concerns over job loss, surveillance, and human decision-making could slow deployment into critically important domains. Pushing on open doors like these can create the kind of friction that makes it a little harder to do the wrong thing.