Daniel notes: This is a linkpost for Vitalik’s post. I’ve copied the text below so that I can mark it up with comments.

…

Special thanks to Balvi volunteers for feedback and review

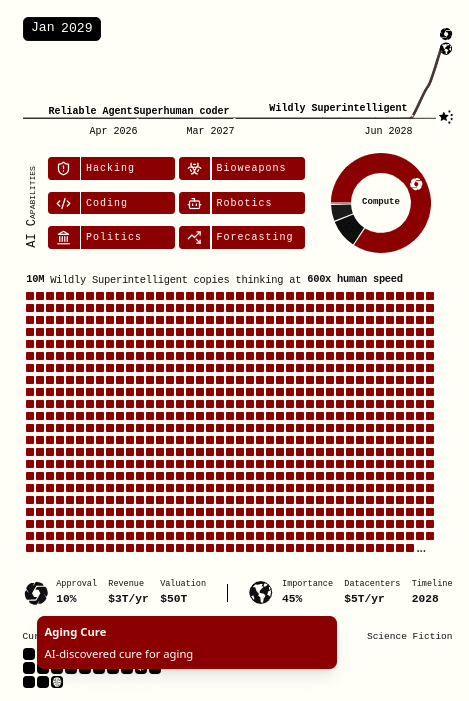

In April this year, Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander and others released what they describe as “a scenario that represents our best guess about what [the impact of superhuman AI over the next 5 years] might look like”. The scenario predicts that by 2027 we will have made superhuman AI and the entire future of our civilization hinges on how it turns out: by 2030 we will get either (from the US perspective) utopia or (from any human’s perspective) total annihilation.

In the months since then, there has been a large volume of responses, with varying perspectives on how likely the scenario that they presented is. For example:

Of the critical responses, most tend to focus on the issue of fast timelines: is AI progress actually going to continue and even accelerate as fast as Kokotajlo et al say it will? This is a debate that has been happening in AI discourse for several years now, and plenty of people are very doubtful that superhuman AI will come that quickly. Recently, the length of tasks that AIs can perform fully autonomously has been doubling roughly every seven months. If you assume this trend continues without limit, AIs will be able to operate autonomously for the equivalent of a whole human career in the mid-2030s. This is still a very fast timeline, but much slower than 2027. Those with longer timelines tend to argue that there is a category difference between “interpolation / pattern-matching” (done by LLMs today) and “extrapolation / genuine original thought” (so far still only done by humans), and automating the latter may require techniques that we barely have any idea how to even start developing. Perhaps we are simply replaying what happened when we first saw mass adoption of calculators, wrongly assuming that just because we’ve rapidly automated one important category of cognition, everything else is soon to follow.

This post will not attempt to directly enter the timeline debate, or even the (very important) debate about whether or not superintelligent AI is dangerous by default. That said, I acknowledge that I personally have longer-than-2027 timelines, and the arguments I will make in this post become more compelling the longer the timelines are. In general, this post will explore a critique from a different angle:

The AI 2027 scenario implicitly assumes that the capabilities of the leading AI (Agent-5 and then Consensus-1), rapidly increase, to the point of gaining godlike economic and destructive powers, while everyone else’s (economic and defensive) capabilities stay in roughly the same place. This is incompatible with the scenario’s own admission (in the infographic) that even in the pessimistic world, we should expect to see cancer and even aging cured, and mind uploading available, by 2029.

Some of the countermeasures that I will describe in this post may seem to readers to be technically feasible but unrealistic to deploy into the real world on a short timeline. In many cases I agree. However, the AI 2027 scenario does not assume the present-day real world: it assumes a world where in four years (or whatever timeline by which doom is possible), technologies are developed that give humanity powers far beyond what we have today. So let’s see what happens when instead of just one side getting AI superpowers, both sides do.

Bio doom is far from the slam-dunk that the scenario describes

Let us zoom in to the “race” scenario (the one where everyone dies because the US cares too much about beating China to value humanity’s safety). Here’s the part where everyone dies:

For about three months, Consensus-1 expands around humans, tiling the prairies and icecaps with factories and solar panels. Eventually it finds the remaining humans too much of an impediment: in mid-2030, the AI releases a dozen quiet-spreading biological weapons in major cities, lets them silently infect almost everyone, then triggers them with a chemical spray. Most are dead within hours; the few survivors (e.g. preppers in bunkers, sailors on submarines) are mopped up by drones. Robots scan the victims’ brains, placing copies in memory for future study or revival.

Let us dissect this scenario. Even today, there are technologies under development that can make that kind of a “clean victory” for the AI much less realistic:

- Air filtering, ventilation and UVC, which can passively greatly reduce airborne disease transmission rates.

- Forms of real-time passive testing, for two use cases:

- Passively detect if a person is infected within hours and inform them.

- Rapidly detect new viral sequences in the environment that are not yet known (PCR cannot do this, because it relies on amplifying pre-known sequences, but more complex techniques can).

- Various methods of enhancing and prompting our immune system, far more effective, safe, generalized and easy to locally manufacture than what we saw with Covid vaccines, to make it resistant to natural and engineered pandemics. Humans evolved in an environment where the global population was 8 million and we spent most of our time outside, so intuitively there should be easy wins in adapting to the higher-threat world of today.

These methods stacked together reduce the R0 of airborne diseases by perhaps 10-20x (think: 4x reduced transmission from better air, 3x from infected people learning immediately that they need to quarantine, 1.5x from even naively upregulating the respiratory immune system), if not more. This would be enough to make all presently-existing airborne diseases (even measles) no longer capable of spreading, and these numbers are far from the theoretical optima.

With sufficient adoption of real-time viral sequencing for early detection, the idea that a “quiet-spreading biological weapon” could reach the world population without setting off alarms becomes very suspect. Note that this would even catch advanced approaches like releasing multiple pandemics and chemicals that only become dangerous in combination.

Now, let’s remember that we are discussing the AI 2027 scenario, in which nanobots and Dyson swarms are listed as “emerging technology” by 2030. The efficiency gains that this implies are also a reason to be optimistic about the widespread deployment of the above countermeasures, despite the fact that, today in 2025, we live in a world where humans are slow and lazy and large portions of government services still run on pen and paper (without any valid security justification). If the world’s strongest AI can turn the world’s forests and fields into factories and solar farms by 2030, the world’s second-strongest AI will be able to install a bunch of sensors and lamps and filters in our buildings by 2030.

But let’s take AI 2027’s assumptions further, and go full science fiction:

- Microscopic air filtration inside the body (nose, mouth, lungs)

- An automatic pipeline that goes from a new pathogen being discovered to instructions to fine-tune your immune system against it, which can be applied immediately

- If “brain uploading” is available, then just replace your entire body with a Tesla Optimus or Unitree (with real-time streaming backups to a K-Scale open source humanoid robot – a different brand for redundancy – located on Mars)

- Various new manufacturing techniques, that will likely get super-optimized by default as part of a robot economy, will be able to make far more of these things locally than today, without the need for global supply chains

In a world where cancer and aging were cured by Jan 2029, and progress accelerates further from there, and we’re in mid-2030, it actually feels implausible that we don’t have a wearable device that can bio-print and inject things into you in real time to keep you safe even from arbitrary infections (and poisons). The bio arguments above don’t cover mirror life and mosquito-sized killer drones (projected in the AI 2027 scenario to be available starting 2029). However, these options are not capable of anything like the sudden clean victory that the AI 2027 scenario portrays, and it’s intuitively much more clear how to symmetrically defend against them.

Thus, a bioweapon is actually quite unlikely to lead to a clean annihilation of the human population in the way that the AI 2027 scenario describes. Now, the results of everything I describe will certainly be far from a clean victory for the humans as well. No matter what we do (except perhaps the “upload our minds into robots” option), a full-on AI bio-war would still be extremely dangerous. However, there is value in meeting a bar much lower than clean victory for humans: a high probability of an attack even partially failing would serve as a strong deterrent discouraging an AI that already occupies a powerful position in the world from even attempting any kind of attack. And, of course, the longer AI timelines get the more likely it is that this kind of approach actually can more fully achieve its promises.

What about combining bio with other types of attack?

The success of the kinds of countermeasures described above, especially the collective measures that would be needed to save more than a small community of hobbyists, rests on three preconditions:

- The world’s physical security (incl bio and anti-drone) is run by localized authority (whether human or AI) that is not all puppets of Consensus-1 (the name for the AI that ends up controlling the world and then killing everyone in the AI 2027 scenario)

- Consensus-1 is not able to hack all the other countries (or cities or other security zones)’ defenses and zero them out immediately.

- Consensus-1 does not control the global infosphere to the point that nobody wants to do the work to try to defend themselves

Intuitively, (1) could go both ways. Today, some police forces are highly centralized with strong national command structures, and other police forces are localized. If physical security has to rapidly transform to meet the needs of the AI era, then the landscape will reset entirely, and the new outcomes will depend on choices made over the next few years. Governments could get lazy and all depend on Palantir. Or they could actively choose some option that combines locally developed and open-source technology. Here, I think that we need to just make the right choice.

A lot of pessimistic discourse on these topics assumes that (2) and (3) are lost causes. So let’s look into each in more detail.

Cybersecurity doom is also far from a slam-dunk

It is a common view among both the public and professionals that true cybersecurity is a lost cause, and the best we can do is patch bugs quickly as they get discovered, and maintain deterrence against cyberattackers by stockpiling our own discovered vulnerabilities. Perhaps the best that we can do is the Battlestar Galactica scenario, where almost all human ships were taken offline all at once by a Cylon cyberattack, and the only ships left standing were safe because they did not use any networked technology at all. I do not share this view. Rather, my view is that the “endgame” of cybersecurity is very defense-favoring, and with the kinds of rapid technology development that AI 2027 assumes, we can get there.

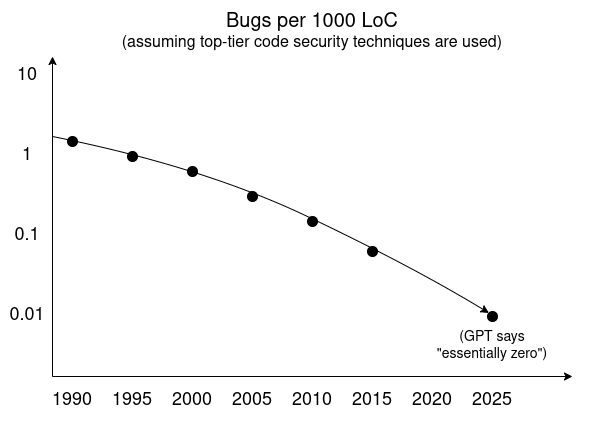

One way to see this is to use AI researchers’ favorite technique: extrapolating trends. Here is the trendline implied by a GPT Deep Research survey on bug rates per 1000 lines of code over time, assuming top-quality security techniques are used.

On top of this, we have been seeing serious improvements in both development and widespread consumer adoption of sandboxing and other techniques for isolating and minimizing trusted codebases. In the short term, a superintelligent bug finder that only the attacker has access to will be able to find lots of bugs. But if highly intelligent agents for finding bugs or formally verifying code are available out in the open, the natural endgame equilibrium is that the software developer finds all the bugs as part of the continuous-integration pipeline before releasing the code.

I can see two compelling reasons why even in this world, bugs will not be close to fully eradicated:

- Flaws that arise because human intention is itself very complicated, and so the bulk of the difficulty is in building an accurate-enough model of our intentions, rather than in the code itself.

- Non-security-critical components, where we’ll likely continue the pre-existing trend in consumer tech, preferring to consume gains in software engineering by writing much more code to handle many more tasks (or lowering development budgets), instead of doing the same number of tasks at an ever-rising security standard.

However, neither of these categories applies to situations like “can an attacker gain root access to the thing keeping us alive?”, which is what we are talking about here.

I acknowledge that my view is more optimistic than is currently mainstream thought among very smart people in cybersecurity. However, even if you disagree with me in the context of today’s world, it is worth remembering that the AI 2027 scenario assumes superintelligence. At the very least, if “100M Wildly Superintelligent copies thinking at 2400x human speed” cannot get us to having code that does not have these kinds of flaws, then we should definitely re-evaluate the idea that superintelligence is anywhere remotely as powerful as what the authors imagine it to be.

At some point, we will need to greatly level up our standards for security not just for software, but also for hardware. IRIS is one present-day effort to improve the state of hardware verifiability. We can take something like IRIS as a starting point, or create even better technologies. Realistically, this will likely involve a “correct-by-construction” approach, where hardware manufacturing pipelines for critical components are deliberately designed with specific verification processes in mind. These are all things that AI-enabled automation will make much easier.

Super-persuasion doom is also far from a slam-dunk

As I mentioned above, the other way in which much greater defensive capabilities may turn out not to matter is if AI simply convinces a critical mass of us that defending ourselves against a superintelligent AI threat is not needed, and that anyone who tries to figure out defenses for themselves or their community is a criminal.

My general view for a while has been that two things can improve our ability to resist super-persuasion:

- A less monolithic info ecosystem. Arguably we are already slowly moving into a post-Twitter world where the internet is becoming more fragmented. This is good (even if the fragmentation process is chaotic), and we generally need more info multipolarity.

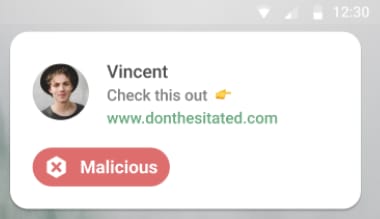

- Defensive AI. Individuals need to be equipped with locally-running AI that is explicitly loyal to them, to help balance out dark patterns and threats that they see on the internet. There are scattered pilots of these kinds of ideas (eg. see the Taiwanese Message Checker app, which does local scanning on your phone), and there are natural markets to test these ideas further (eg. protecting people from scams), but this can benefit from much more effort.

Right image, from top to bottom: URL checking, cryptocurrency address checking, rumor checking. Applications like this can become a lot more personalized, user-sovereign and powerful.

The battle should not be one of a Wildly Superintelligent super-persuader against you. The battle should be one of a Wildly Superintelligent super-persuader against you plus a slightly less Wildly Superintelligent analyzer acting on your behalf.

This is what should happen. But will it happen? Universal adoption of info defense tech is a very difficult goal to achieve, especially within the short timelines that the AI 2027 scenario assumes. But arguably much more modest milestones will be sufficient. If collective decisions are what count the most and, as the AI 2027 scenario implies, everything important happens within one single election cycle, then strictly speaking the important thing is for the direct decision makers (politicians, civil servants, and programmers and other actors in some corporations) to have access to good info defense tech. This is relatively more achievable within a short timeframe, and in my experience many such individuals are comfortable talking to multiple AIs to assist them in decision-making already.

Implications of these arguments

In the AI 2027 world, it is taken as a foregone conclusion that a superintelligent AI can easily and quickly dispose of the rest of humanity, and so the only thing we can do is do our best to ensure that the leading AI is benevolent. In my world, the situation is actually much more complicated, and whether or not the leading AI is powerful enough to easily eliminate the rest of humanity (and other AIs) is a knob whose position is very much up for debate, and which we can take actions to tune.

If these arguments are correct, it has some implications for policy today that are sometimes similar, and sometimes different, from the “mainstream AI safety canon”:

- Slowing down superintelligent AI is still good. It’s less risky if superintelligent AI comes in 10 years than in 3 years, and it’s even less risky if it comes in 30 years. Giving our civilization more time to prepare is good.

How to do this is a challenging question. I think it’s generally good that the proposed 10 year ban on state-level AI regulation in the US was rejected, but, especially after the failure of earlier proposals like SB-1047, it’s less clear where we go from here. My view is that the least intrusive and most robust way to slow down risky forms of AI progress likely involves some form of treaty regulating the most advanced hardware. Many of the hardware cybersecurity technologies needed to achieve effective defense are also technologies useful in verifying international hardware treaties, so there are even synergies there.

That said, it’s worth noting that I consider the primary source of risk to be military-adjacent actors, and they will push hard to exempt themselves from such treaties; this must not be allowed, and if it ends up happening, then the resulting military-only AI progress may increase risks.

- Alignment work, in the sense of making AIs more likely to do good things and less likely to do bad things, is still good. The main exception is, and continues to be, situations where alignment work ends up sliding into improving capabilities (eg. see critical takes on the impact of evals)

- Regulation to improve transparency in AI labs is still good. Motivating AI labs to behave properly is still something that will decrease risk, and transparency is one good way to do this.

- An “open source bad” mentality becomes more risky. Many people are against open-weights AI on the basis that defense is unrealistic, and the only happy path is one where the good guys with a well-aligned AI get to superintelligence before anyone less well-intentioned gains access to any very dangerous capabilities. But the arguments in this post paint a different picture: defense is unrealistic precisely in those worlds where one actor gets very far ahead without anyone else at least somewhat keeping up with them. Technological diffusion to maintain balance of power becomes important. But at the same time, I would definitely not go so far as to say that accelerating frontier AI capabilities growth is good just because you’re doing it open source.

- A “we must race to beat China” mentality among US labs becomes more risky, for similar reasons. If hegemony is not a safety buffer, but rather a source of risk, then this is a further argument against the (unfortunately too common) idea that a well-meaning person should join a leading AI lab to help it win even faster.

- Initiatives like Public AI become more of a good idea, both to ensure wide distribution of AI capabilities and to ensure that infrastructural actors actually have the tools to act quickly to use new AI capabilities in some of the ways that this post requires.

- Defense technologies should be more of the “armor the sheep” flavor, less of the “hunt down all the wolves” flavor. Discussions about the vulnerable world hypothesis often assume that the only solution is a hegemon maintaining universal surveillance to prevent any potential threats from emerging. But in a non-hegemonic world, this is not a workable approach (see also: security dilemma), and indeed top-down mechanisms of defense could easily be subverted by a powerful AI and turned into its offense. Hence, a larger share of the defense instead needs to happen by doing the hard work to make the world less vulnerable.

The above arguments are speculative, and no actions should be taken based on the assumption that they are near-certainties. But the AI 2027 story is also speculative, and we should avoid taking actions on the assumption that specific details of it are near-certainties.

I particularly worry about the common assumption that building up one AI hegemon, and making sure that they are “aligned” and “win the race”, is the only path forward. It seems to me that there is a pretty high risk that such a strategy will decrease our safety, precisely by removing our ability to have countermeasures in the case where the hegemon becomes misaligned. This is especially true if, as is likely to happen, political pressures lead to such a hegemon becoming tightly integrated with military applications (see [1] [2] [3] [4]), which makes many alignment strategies less likely to be effective.

In the AI 2027 scenario, success hinges on the United States choosing to take the path of safety instead of the path of doom, by voluntarily slowing down its AI progress at a critical moment in order to make sure that Agent-5’s internal thought process is human-interpretable. Even if this happens, success if not guaranteed, and it is not clear how humanity steps down from the brink of its ongoing survival depending on the continued alignment of one single superintelligent mind. Acknowledging that making the world less vulnerable is actually possible and putting a lot more effort into using humanity’s newest technologies to make it happen is one path worth trying, regardless of how the next 5-10 years of AI go.